Sunday 6 September 2015

Wednesday 19 August 2015

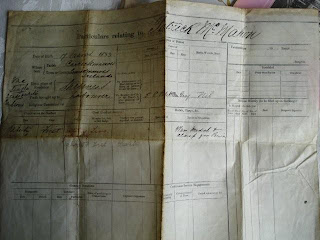

McMahon Family

When the McMahons were the chief tribe of Farney in Monaghan until Elizabeth 1 gave the county to the Earl of Essex

FARNEY–MR. TRENCH’S ’REALITIES.’

When the six Ulster counties were confiscated, and the natives were all deprived of their rights in the soil, the people of the county Cavan resolved to appeal for justice to the English courts in Dublin. The Crown was defended by Sir John Davis. He argued that the Irish could have no legal rights, no property in the land, because they did not enclose it with fences, or plant orchards. True, they had boundary marks for their tillage ground; but they followed the Eastern custom in not building ditches or walls around their farms. They did not plant orchards, because they had too many trees already that grew without planting. The woods were common property, and the apples, if they had any, would be common property too, like the nuts and the acorns.

The Irish were obliged to submit to the terms imposed by the conquerors, glad in their destitution to be permitted to occupy their own lands as tenants at will. The English undertakers, as we have seen, were bound to deal differently with the English settlers; but their obligations resolved themselves into promises of freeholds and leases which were seldom granted, so that many persons threw up their farms in despair, and returned to their own country.

In the border county of Monaghan, we have a good illustration of the manner in which the natives struggled to live under their new masters. The successors of some of those masters have in modern times taken a strange fancy to the study of Irish antiquities. Among these is Evelyn P. Shirley, Esq., who has published ’Some Account of the Territory or Dominion of Farney.’ The account is interesting, and, taken in connection with the sequel given to the public by his agent, Mr. W. Steuart Trench, it furnishes an instructive chapter in the history of the land war. The whole barony of Farney was granted by Queen Elizabeth to Walter Earl of Essex in the year 1576, in reward for the massacres already recorded. It was then an almost unenclosed plain, consisting chiefly of coarse pasturage, interspersed with low alder—scrub. When the primitive woods were cut down for fuel, charcoal, or other purposes, the stumps remained in the ground, and from these fresh shoots sprang up thickly. The clearing out of these stumps was difficult and laborious; but it had to be done before anything, but food for goats, could be got out of the land. This was ’the M’Mahons’ country,’ and the tribe was not wholly subdued till 1606, when the power of the Ulster chiefs was finally broken. The lord deputy, the chancellor, and the lord chief justice passed through Farney on their way to hold assizes for the first time in Derry and Donegal. They were protected by a guard of ’seven score foot, and fifty or three score horse, which,’ wrote Sir John Davis, ’is an argument of a good time and a confident deputy; for in former times (when the state enjoyed the best peace and security) no lord deputy did ever venture himself into those parts, without an army of 800 or 1000 men.’ At this time Lord Essex had leased the barony of Farney to Evor M’Mahon for a yearly rent of 250 l. payable in Dublin. After fourteen years the same territory was let to Brian M’Mahon for 1,500 l. In the year 1636, the property yielded a yearly rent of 2022 l. 18 s. 4 d. paid by thirty—eight tenants. A map then taken gives the several townlands and denominations nearly as they are at present. Robert Earl of Essex, dying in 1646, his estates devolved on his sisters, Lady Frances and Lady Dorothy Devereux, the former of whom married Sir W. Seymour, afterwards Marquis of Hertfort, and the latter Sir Henry Shirley, Bart., ancestor of the present proprietor of half the barony. Ultimately the other half became the property of the Marquis of Bath. At the division in 1690, each moiety was valued at 1313 l. 14 s. 4—1/2 d. Gradually as the lands were reclaimed by the tenants, the rental rose. In 1769 the Bath estate produced 3,000 l., and the Shirley estate 5,000 l. The total of 8,000 l. per annum, from this once wild and barren tract, was paid by middlemen. The natives had not been rooted out, and during the eighteenth century these sub—tenants multiplied rapidly. According to the census in 1841 the population of the barony exceeded 44,000 souls, and they contributed by their industry, to the two absentee proprietors, the enormous annual revenue of 40,000 l., towards the production of which it does not appear that either of them, or any person for them, ever invested a shilling.

Mr. S. Trench was amazed to find ’more than one human being for every Irish acre of land in the barony, and nearly one human being for every 1 l. valuation per annum of the land.’ The two estates join in the town of Carrickmacross. When Mr. Trench arrived there, March 30, 1843, to commence his duties as Mr. Shirley’s agent, he learned that the sudden death of the late agent in the court—house of Monaghan had been celebrated that night by fires on almost every hill on the estate, ’and over a district of upwards of 20,000 acres there was scarcely a mile without a bonfire blazing in manifestation of joy at his decease.’ Mr. Trench says, the tenants considered themselves ground down to the last point by the late agent. As he relates the circumstances, the people would seem to be a very savage race; and he gives other more startling illustrations to the same effect as he proceeds. But here, as elsewhere, he does not state all the facts, while those he does state are most artistically dressed up for sensational effect, Mr. Trench himself being always the hero, always acting magnificently, appearing at the right place and at the right moment to prevent some tremendous calamity, otherwise inevitable, and by some mysterious personal influence subduing lawless masses, so that by a sudden impulse, their murderous rage is converted into admiration, if not adoration. Like the hearers of Herod or of St. Paul, when he flung the viper off his hand, they are ready to cry out, ’He is a god, and not a man.’ Of course he, as a Christian gentleman, was always ’greatly shocked,’ when these poor wretches offered him petitions on their knees. Still he relates every case of the kind with extraordinary unction, and with a picturesqueness of situation and detail so stagey that it should make Mr. Boucicault’s mouth water, and excite the envy of Miss Braddon. Not even she can exceed the author of ’Realities of Irish Life,’ in prolonging painful suspense, in piling up the agony, in accumulating horrors, in throwing strong lights on one side of the picture and casting deep shade on the other.

The Land-War In Ireland 1870

’Do you pay anything for the ticket of leave to cut?–Yes, I do; I have not a ticket unless I pay 6 d. for it.

’That is over and above the 4 s. 6 d.?–Yes.

’Did you ever pay more than 6 s. 8 d. for the bog in the late agent’s time?–He took the good bog off us; we were paying 6 s. 8 d. for it. They left us to the bad bog, and we do not pay so high for that.

’Was the good bog dearer or cheaper than the bad bog at 4 s. 6 d.?–Half a rood of the good bog was worth half an acre or an acre of the other. The bad bog smokes so we have often to leave the house: we cannot stay in it unless there is a good draught in the chimney.’

The Rev. Thomas Smollan, P.P., has published a letter to the Earl of Dunraven, a Catholic Peer, to whom Mr. Trench has dedicated his book. In this letter the parish priest of Farney says:–

’In pages 63 and 64 Mr. Trench tells his readers that on the very night the news of the late agent’s sudden death, in the county courthouse of Monaghan, reached Carrickmacross, “fires blazed on almost every hill on the Shirley estate, and over a district of more than 20,000 acres there was scarcely a mile without a bonfire blazing in manifestation of joy at his decease.” This paragraph, my lord, taken by itself and unexplained in any way, would at once imply that the people were inhuman, almost savages, whom Mr. Trench was sent to tame–that they were insensible to the agent’s sudden death, a death so sudden that it would make an enemy almost relent. Mr. Trench assigns no cause for this strange proceeding except what we read in page 64, and what he learned from the chief clerk, viz., “that the people were much excited, that they were ground down to the last point by the late agent, and they were threatening to rise in rebellion against him,” &c. One would think that Mr. Trench having learned so much on such authority, would have set to work to try and find out the cause of the discontent and apply a remedy. He does not say in his book that he did so, but seems still unable to understand this to him incomprehensible proceeding. However, I am of opinion that Mr. Trench knew the whole of it, if not then at all events before “The Realities” saw the light, for in a speech of his, when Lord Bath visited Farney (page 383), he said, “A dog could not bark on the estate without it coming to his knowledge.” And therefore I say that a man so inquisitive as to find out the barking of a dog on the Bath estate, who had so many sources of information close at hand, could not have been long without knowing the causes of the “excitement, threatened rebellion, bonfires, &c., on the Shirley estate,” if he had only wished for the information. Either he knew the cause of all this when he wrote his book, or he did not. If he did, I say he was bound in fair play to tell it to the public; if he did not know it his self—laudation in his speech goes for nought. But, my lord, with your permission, I will inform your lordship, Mr. Trench, and the public, as to some of the causes of so remarkable an occurrence, which could not pass unobserved by Mr. Trench. At the memorable election of 1826, Evelyn John Shirley, Esq., and Colonel Leslie, father of the present M.P., contested the county of Monaghan, and the former brought all his influence to bear on his tenants to vote for himself (Shirley) and Leslie, who coalesced against the late Lord Rossmore. The electors said “they would give one vote for their landlord, and the other they would give for their religion and their country;” the consequence was, Shirley and Westenra were returned, and Leslie was beaten. Up to this time Mr. Shirley was a good landlord, and admitted tenant—right to the fullest extent on the property, but after that election he never showed the same friendly feelings towards the people. Soon after the election Mr. Humphrey Evatt, the agent, died, and was succeeded in the agency by Mr. Sandy Mitchell, who very soon set about surveying and revaluing the estate, of course at the instance of his master, Evelyn John Shirley, Esq. He performed the work of revaluation, &c., and the result was that the rents were increased by one—third and in some cases more. The bog, too, which up to this time was free to the tenants, was taken from them and doled out to them in small patches of from twenty—five to forty perches each, at from 4 l. to 8 l. per acre. At the instance of the then parish priest, President Reilly, Mr. Shirley gave 5 l. per year to a few schools on his property, without interfering in any way with the religious principles of the Catholics attending these schools; but the then agent insisted on having the authorised version of the Bible, without note or comment, read in those schools by the Catholic children. The bishop, the Most Rev. Dr. Kernan, could not tolerate such a barefaced attempt at proselytism, and insisted on the children being withdrawn from the schools. For obeying their bishop in this, the Catholic parents were treated most unsparingly. I have before me just now a most remarkable instance of the length to which this gentleman carried his proselytising propensities, which I will mention. In the vestry, or sacristy, attached to Corduff Chapel, was a school taught by a man named Rush, altogether independent of the schools aided by Mr. Shirley, and by largely subsidising the teacher, the then agent actually introduced his proselytism into that school too. The priests and people tried legal means to get rid of the teacher, but without success, and in the end the people came by night and knocked down the sacristy, so that in the morning when the teacher came he had no house to shelter him. The Catholics were then without a school, and in order to provide the means of education for them the Rev. F. Keone, administrator, under the Most Rev. Dr. Kernan, applied for aid to the Commissioners of National Education, and obtained it; but where was he to procure building materials? The then agent, in his zeal for “converting” Catholics, having issued an order forbidding the supplying of them from any part of the Shirley estate, which extends over an area of fifteen miles by ten, Father Keone went on the next Sunday to the neighbouring chapels outside the Shirley estate, told his grievances, and on the next day the people came with their horses and carts and left sand, lime, and stones in sufficient quantities to build the house inside the chapel—yard. The priest and people thought it necessary to “thatch” their old chapel, and, though strange it may seem, the agent actually served an ejectment process on the father of the two boys who assisted the priest to make the collection at the chapel door for so absolutely necessary a work. I may add, this man owed no rent. Lastly, the then agent was in the habit of arranging matrimonial alliances, pointing out this girl as a suitable match for that boy, and the boy must marry the girl or give up his farm. These facts being true, my lord, and more which I might state, but that I have trespassed too much already on your lordship’s time, I ask you, my Lord Dunraven–I ask any impartial man, Irishman or Englishman–for whom Mr. Trench wrote his “book,” is it strange or wonderful that the Catholic people, so treated, would rejoice–would have bonfires on the hill tops at their deliverance from such conduct? I flatter myself that you, my lord–that the learned reading public–that the English people would sympathise with any people so treated for conscience’ sake; and having pronounced the sentence of condemnation against Mr. Trench for not having noticed these facts, that you will direct your name to be erased from the “book.” I have the honour to remain, my lord, with the most profound respect, your lordship’s faithful servant.’

McMahon Faamily

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)